100 Years Since the Great Kanto Earthquake – Are You Prepared for Disasters?

Moderator Speakers

- <Moderator>Mikiko Takahashi,Ph.D. Director of JTA, Manager of R&D Division of Company Inc

- <Speakers1>“Toilets and Human Waste Management During the Great Kanto Earthquake”

Mr. Eiki Morita (JTA steering committee member, Toilet researcher/ toilet history) - <Speakers2>“Stockpile status of Emergency Toilets in 2023”

Mr. Kan-ichi Adachi (JTA steering committee member, Excelsior Inc. President)

Toilets and Human Waste Management During the Great Kanto Earthquake

Pre-Earthquake Toilet Situation

I will talk about the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, but not in terms of the entire Kanto region. Instead, I will focus on the toilet situation in a very limited area of Tokyo, where relatively more records remain.

Tokyo became the Tokyo Metropolis (Tokyo-to) in 1943. Before that, it was referred to as Tokyo Prefecture (Tokyo-fu). In 1889, 15 wards were established in the eastern part of what is now Tokyo.

During the Taisho era (1912–1926), human waste was not collected, making it a serious nuisance. According to records from 1918, five years before the Great Kanto Earthquake, human waste collection had completely ceased. Citizens in trouble began to dispose of the human waste by drilling holes in the bottom of their latrine pits to allow the waste to seep underground, or by secretly dumping it into the sewer system at night.

At that time, gutters and rivers were also broadly referred to as sewage.

People began secretly dumping human waste into gutters and other areas at night, leading to a flood of complaints to the Tokyo municipal office and ward offices on a daily basis.

This problem was particularly serious in the Yamanote district (up town).

The area was elevated and had once been home to many feudal lord estates and temples. As a result, land plots were large, and the population density was low. Due to the elevation, manually transporting human waste was extremely difficult.

Thus, the efficiency of human waste collection in the Yamanote district was very poor.

In the Yamanote area, there were relatively few fires during the Great Kanto Earthquake, resulting in comparatively less damage.

In contrast, the Shitamachi area (down town) was developed by reclaiming low-lying wetlands into a district for artisans and merchants. The plots of land were small, and the population density was high. The area was blessed with waterways such as rivers and canals, allowing for the efficient transportation of human waste by boat. Because of this, human waste collection was highly efficient. However, this region experienced numerous fires, leading to serious damage from the earthquake.

Just before the Great Kanto Earthquake, the problem of human waste collection was beginning to worsen in the Yamanote area where collection efficiency was lower.

During the Edo period (17th to 19th centuries), farmers from rural areas surrounding the city would come into the urban area to collect human waste from familiar households and take it back with them. Since the process was carried out by hand, the maximum distance for transportation was about 10 to 20 kilometers.

They delivered crops to the market and, on their way back, collected human waste.

In 1868, the Edo period ended, and as urbanization progressed, cities expanded.

As a result, the boundary between urban and rural areas shifted toward the rural side, allowing farmers to obtain the necessary human waste without having to travel all the way to the older city districts.

Because of this, the Yamanote area, which had long been an urban district, became a region where the collection of human waste stagnated.

Before the Great Earthquake, numerous complaints were raised, and measures were demanded from the Tokyo municipal government.

In the year before the Great Earthquake, in 1922, Tokyo City Councilor Saegusa submitted an inquiry regarding the human waste issue.

In 1919, four years before the Great Kanto Earthquake, the Tokyo City government (which is one of the cities in the Tokyo prefecture) provided free human waste collection service in areas where the collections were most stagnant.

According to a survey conducted by Tokyo City, there were very few landlords who charged farmers for collecting human waste. Instead, it was more common for landlords to pay the farmers.

During the Edo period, landlords and house owners allowed farmers to collect human waste in exchange for payment or agricultural products, treating it as a valuable commodity. However, by the time this survey was conducted by Tokyo City, such practices had largely disappeared.

Yet, some farmers continued to collect human waste for free due to long-standing relationships with landlords.

As a business, individual farmers rarely traveled to urban areas for collection. Instead, most of the operations were handled by companies or fertilizer cooperatives.

It is estimated that 11,000 koku (1 koku is approximately 180 liters) of human waste was discharged daily in Tokyo City.

Of this amount, the city planned to collect and dispose of 2,000 koku, which could not be handled by private contractors. To transport the large volume to the suburbs, the plan was to use railways.

Additionally, a sewage treatment plant was built in Mikawashima and had already been operational before the earthquake, so sewer pipes were being installed to direct waste there.

The city designated five districts—Koishikawa, Hongo, Ushigome, Shitaya, and Asakusa—where waste collection would be directly managed by Tokyo City due to severe stagnation. A total of 295 personnel were assigned to this task, both directly and indirectly.

In this waste collection process, the Tokyo City government charged residents a fee.

At this point, human waste transitioned from a commodity to a type of waste that required paid disposal.

However, the traditional method still remained, and both approaches were in use.

Amidst this situation, the Great Earthquake struck.

Toilet Situation After the Earthquake

On Saturday, September 1, 1923, at 11:58 AM, the earthquake occurred. At that time, Saturday afternoons were a half-day off, so many people had already left their offices and workplaces.

According to records, the initial priority was given to relief efforts for the disaster victims.

The disappearance and collapse of bridges, as well as drifting debris, blocked transportation.

At that time, Tokyo had a highly developed water transportation system, so the inability to use the rivers seemed to be an even more serious problem than it would be today.

Fear of rumors and false information made it difficult to gather workers.

There was apparently an automobile garage at Suidobashi, where six cars were burned, which was quite a considerable shock.

The city of Tokyo had 262 public toilets, but most of them—210 in total—were damaged.

The remaining 52 were mainly located in the Yamanote area, which suffered less damage.

As for automobiles, six were destroyed at the Suidobashi garage, leaving 24 still available.

Regarding transport buckets and barrels, roughly half of them were lost.

During the Great Kanto Earthquake, fire damage was severe, and the fires continued until around September 3.

A record from the 4th, when the fires had mostly been extinguished, states that temporary emergency toilets were set up in refugee gathering areas, cleanup teams were organized, and cleaning and disinfection were carried out.

Due to the severe shortage of toilets in the burned-out areas, efforts were made to increase the number of temporary toilets, with around 400 set up throughout the city. In addition to those installed by the city, there were also a considerable number of temporary toilets built by various individuals and groups. There are records indicating that the University of Tokyo also constructed many temporary toilets for the evacuees.

Both the records from the University of Tokyo and the documents left by the authorities refer to these as “Temporary Toilets.”

The concept of temporary toilets already existed in this era.

However, due to insufficient night soil collection, there were delays in the night soil collection process. On the 8th, one week after the earthquake, the stagnation became significant, and the city of Tokyo developed a night soil disposal plan. Before the earthquake, 2,000 koku of waste had been collected, but nearly half of the equipment had been lost or destroyed, making the process difficult. Since the population was moving or decreasing, the daily excretion amount was estimated to be 7,500 koku, of which 2,000 koku would be collected for free by the city or ward’s direct operation. The rest would be collected for a fee, as outlined in the plan.

Specifically:

(1) Temporary toilets will be installed in evacuation assembly areas, and waste will be collected free of charge.

(2) With support from various groups, such as the youth association and the local veterans’ association, efforts will be made to remove the waste. A collection fee will be paid .

(3) Coordination will be made with the Metropolitan Police Department, the prefectural government, and the Ministry of Home Affairs to procure necessary equipment. Additionally, calls for assistance will be made to various organizations to get supports for waste collection.

(4) The waste will then be transported by boat or discharged into the sewer system.

In 1922, the year before the earthquake, the Mikawashima sewage treatment plant began operation, but it was damaged by the earthquake. However, since the damage was minimal, the plan to discharge sewage into the Mikawashima treatment plant was considered. On September 10, this plan was communicated to the district heads.

The city of Tokyo rented 10 automobiles and 60 horse-drawn carts for the transportation of human waste and distributed them to each district. On September 12, the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department provided six automobiles to assist with the sewage transportation. On September 14, the Ministry of Home Affairs also provided 10 automobiles as additional support.

By the second week after the earthquake, the sewage problem in the Yamanote area, which had suffered minimal fire damage, was almost resolved.

On September 22, in the Shitamachi areas where many homes had been destroyed by the fire, people began to build shacks and start living there, but the stagnation in sewage collection became increasingly serious.

The City of Tokyo contracted with fertilizer associations and had them carry out the sewage removal.

The situation was communicated to the district heads.”

September 25. With the necessary tools for human waste collection having become available, it became possible to collect 5,000 koku per day. Additionally, the railway transportation of human waste and the use of human waste disposal sites were resumed. As a result, a considerable amount could be collected, and it also became possible to transport it to the suburbs. On November 25, the free emergency human waste collection service was terminated.

Toilets at that time

Public toilets today were referred to as “street toilets” at the time, and the city of Tokyo managed 262 locations.

There were “upper cleaning” and “lower cleaning” tasks. Upper cleaning involved cleaning the interior, while lower cleaning was the removal of human waste.

Interior cleaning was carried out 2 to 4 times a day.

For waste removal, 10 districts were directly managed, while 5 districts used contractors for waste collection, with supervisors overseeing the work.

During special periods, additional workers were assigned, and deodorants were also sprayed.

The city of Tokyo ensured that proper maintenance was carried out.

The earthquake destroyed 210 street toilets. 52 of them in the Yamanote area are still operational. A five-year reconstruction plan was made, with the goal of repairing 42 toilets each year, totaling the 210 damaged ones. However, in reality, due to budget shortages, the plan was delayed, and by 1930, only 132 toilets had been repaired. There are not many good records about what kind of toilets were built, but a public toilet near Kyobashi is featured in a book from 1937.

It is quite a stylish toilet, a single-story building designed like a park gazebo, with a resting area inside that has benches. There are no toilets on the first floor. The toilet is located downstairs, accessible via stairs. There is only one entrance, unisex toilet with four toilet cubicles (squat style at the time), and urinals arranged along the circular wall.

The Marukobashi public toilet in Denenchofu. Although this was not built as part of Tokyo’s reconstruction project, it was also featured in the book mentioned above. This one is separated by gender. The men’s toilet has one toilet cubicle and four urinals, while the women’s toilet has two toilet cubicles.

The public toilet in Ikenohata of Ueno Park was unisex. There is one cubicle, and an urinal space without partitions where 2-3 people can use it simultaneously. This seems to have been built as part of the reconstruction efforts following the earthquake.

Conclusion

The records of those involved in cleaning, not just waste disposal, include positions such as cleaning supervisors, captains, engineers, and car drivers. Among those 275 people, 101 had lost their homes. Nearly half of them, despite being disaster victims themselves, were still engaged in cleaning and other duties. I have great admiration for their dedication.

Stockpile status of Emergency Toilets in 2023

survey on the stockpiling rate of handy or portable toilets

I am a member of the steering committee of the Japan Toilet Association, the deputy secretary of the Disaster and Temporary Toilet Study Group, and the leader of the Portable Toilet Group.

I am also the president of a company called Excelsior, which manufactures portabley toilets.

Every three years, we conduct a survey on the stockpiling rate of handy or portable toilets, at the same location and with the same number of participants. This is the third time we have conducted this survey.

The locations we select are the prefectures predicted to be affected by the earthquake directly beneath the capital or the Nankai Trough earthquake.

The areas related to the earthquake directly beneath the capital are Tokyo and the three neighboring prefectures—Kanagawa, Chiba, and Saitama.

The areas related to the Nankai Trough earthquake are six prefectures: Shizuoka, Aichi, Mie, Wakayama, Tokushima, and Kochi. A survey was conducted towards 100 people from each prefecture, totaling 1,000 respondents. The stockpiling rate of handy or portable toilets was 15.5% in the first survey in 2017, 19.5% in 2020, and 22.2% in 2023, showing a gradual increase. However, we still believe that the number is still too low.

In terms of gender ratio, women have a higher rate of stockpiling than men. Regarding toilets, women show much higher interest than men.

By age group, there were more responses indicating stockpiling among those in their 20s. In contrast, very few people in their 50s reported stockpiling. I guess that people in their 50s have many expenses, such as education costs for their children, and therefore spend very little on stockpiling for toilets.

In terms of prefectures, Tokyo and Shizuoka have very high stockpiling rates. Shizuoka has been preparing for stockpiles for a long time as it has been pointed out that there is a possibility of a major earthquake soon after the world war Ⅱ. Tokyo, due to concerns about a potential major earthquake directly under the capital, seems to have a high level of awareness. In contrast, Kochi Prefecture has been pointed out as being at risk of the Nankai Trough earthquake, yet its stockpiling rate is low. In less urbanized areas, many people feel that even without stockpiled toilets, they can dig a hole in their backyard to relieve themselves, and this mindset may be reflected in these numbers.

In 2020, there wasn’t much difference between single-family homes and multi-family ones, but in this year’s 2023 survey, the storage rate in multi-family homes has significantly increased. This applies generally to disaster preparedness, and there is also a heightened awareness of stockpiling items like water in multi-family homes.

If the elevator in a high-rise apartment building stops, residents on the upper floors face significant difficulties with access to water and toilets. I think this kind of understanding has gradually spread.

Compared to people living alone, those living with their family tend to have more stockpiled supplies.

We also asked about food and water, in addition to toilets.

In a survey conducted three years ago, about 50% of households reported having emergency food supplies, and around 60% said they had stored water.

This year’s survey shows a 4.2-point decrease in the emergency food stockpiling rate. The water stockpiling rate has also decreased by 2.6 points. After experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic and the prolonged war in Ukraine, people seem to have become quite accustomed to various crises.

It can be imagined that the motivation to prepare for disasters has decreased, but the stockpiling rate for supplies other than toilets has declined. The stockpiling for toilets has increased by 3 points. Compared to other supplies, the result seems to be relatively good. The reasons for stockpiling emergency toilets were largely due to feelings of anxiety or because it was featured on TV.

When asked about the disaster that led them to start stockpiling emergency toilets, the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 comes up very frequently.

However, it’s been almost 13 years since the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Recently, there has been a significant increase in interest regarding flooding.

We asked how many they have stocked up on emergency toilets. About 40% of people have enough for 0 to 4 uses. If we include those with 5 to 9 uses, it adds up to more than half. As for how many emergency toilets are needed, it’s said that one person requires five uses per day. When considering a one-week stockpile, that would be 35 uses for one person. Even for those who have stockpiled, the number is still insufficient.

When asked where they purchased it, the answer was overwhelmingly from the internet. In addition, many people also purchase it at home improvement stores, drugstores, and supermarkets.

When asked if they know how to use an emergency toilet, 7.7% have used it, 59.5% have not used it but have read the instruction manual, and 32.9% have never read the manual.

Unless people use it, it’s impossible to understand the differences in usage methods between products, so I hope they try it out.

When asked those who do not have emergency toilets in stock, the reason for not stocking them, many people answered that they didn’t have a particular reason.

Information about the difficulties related to toilet use during disasters has not yet fully reached the public.

Without proper toilets for disaster situations, not only will it be difficult for individuals to relieve themselves, but there is also the potential for infection and secondary disasters caused by waste.

When asked about future stockpiling plans, about 40% of people expressed an intention to stockpile. Around 20% answered that they have no intention to stockpile, and when combined with those who were unsure, more than half of the people do not have the intention to prepare stockpiles.

Approximately 80% of people were aware that toilets might become unusable during major earthquakes or floods.

Those who knew that toilets might be unusable during disasters had a 20-point higher rate of having emergency toilets in their stockpiles.”

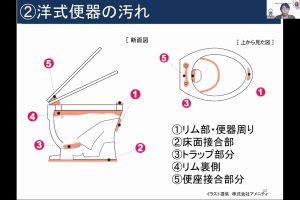

There are various types of emergency toilets

There are various types of emergency toilets.

An example of the Manhole Toilet

An example of the Temporary Toilet

There are some issues, though. The manhole cover cannot be opened without special tools, and if the water flow is weak, waste may accumulate.

A temporary toilet is a portable cubicle. The structure of a temporary toilet includes a tank beneath it where about 400 liters of waste can accumulate, which is then sucked up by a vacuum truck. However, since flush toilets have become widespread, there are fewer vacuum trucks available.

Since temporary toilets must be transported by truck, they cannot be delivered immediately after a disaster occurs. It is difficult for both manhole toilets and temporary toilets to be distributed quickly when a disaster strikes. Therefore, it is important to stockpile handy or portable toilets at home. A flush toilet, even a water-saving one, requires around 5 liters of water, but during a disaster, it is often difficult to secure enough water.

An example of the Portable Toilet

An example of the Handy Toilet

A portable toilet, in simple terms, is one with a seat. The toilet seat can be made from various materials such as cardboard, plastic, or metal.

A handy toilet, on the other hand, does not have a seat. In the event of a disaster where water cannot be flushed in a toilet, but you can still sit on the toilet seat, a portable toilet can be attached to the toilet for use.

Handy or portable toilets are used with treatment agents that have functions such as coagulation, sterilization, and deodorization. The treatment agents can either be sprinkled after use or placed in advance.

Our product uses tablet-shaped treatment agents that are placed in advance. They have strong sterilizing power and can be used for disinfecting vomit, blood, and other bodily fluids. The set also includes a poncho, making it suitable for use outdoors.

Regarding toilets prepared for emergencies, the government recommends stocking enough for a week.

During the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake, in areas where liquefaction caused manholes to float, it took two months for full recovery.

If a sewage treatment plant is affected by a disaster, it can take several months to restore. Sewage treatment plants are often located near the sea, so they can also be vulnerable to tsunami damage. Based on such experiences, it can be said that having stockpiling of emergency toilets is extremely important.

Q&A

(Q1: HO) How does Mr. Morita gather information about toilets in the past?

(A1: Morita) I don’t use libraries much. The foundation of this presentation is mostly based on reports created by the city of Tokyo. Recently, I’ve also obtained some information through the internet.

As for the reliability of the information, the reality is that there aren’t enough data remaining to cross-check multiple sources.

(Q2: HO) Question for Mr. Adachi: What is the expiration period of the toilet treatment agents in stock?

(A2: Adachi) Our products have a shelf life of 5 years, but many products from other companies are now good for 10 years.

If you stockpile for 10 years, the responsible person at the company may change, and there’s a concern that the basis for the quantity calculations could be lost.

Even after 5 years of storage, the quality of our product has not deteriorated, so we collect them and distribute them for free to mountaineers and participants in local government disaster prevention events.

We are also exploring ways to use them for social contribution in countries where infectious diseases are spreading.

(Q3: Takahashi) Even for handy toilets, the prices vary. What are the differences?

(A3: Adachi) There are products available at very low prices. High molecular absorbent polymers are used to solidify the human excrement. These are also used in diapers and sanitary products, where the focus is on absorption speed and capacity.

However, for handy toilets, it is also important whether the solidified state can last until disposal after use. In some terrible cases, a solidified material turns back into liquid within a day.

(Q4: Kawauchi) In the Edo, Meiji, and Taisho periods (from the 17th century to the early 20th century), how did people in urban areas wipe themselves after defecation?

(A4: Morita) It probably varied depending on the economic status of the residents, but there are records that suggest paper was beginning to be used. As time passed, it is reasonable to think that the use of paper became more widespread.

I guess that the stool of people in the past was quite different from that of modern people. Modern people drink much more water, I think. In the past, fetching water was hard labor, so people likely didn’t drink as much water.

As a result, urine would have been more inspissated, and because their waste was different from that of modern people, I think the way the area around the anus got soiled during excretion would also have been different.

(Adachi)

Regarding toilets for disaster preparedness, I would like to provide additional information as there was some lack of explanation.

Waste containing excrement is treated as burnable trash, but during a disaster, there is a high possibility that trash collection may not be conducted for an extended period. Therefore, there is a high likelihood that it will need to be stored for a long time. In hot weather, methane gas and other gases may be generated, and there have been reports of bags bursting. I want you to be aware of this possibility.